Background

In this post, I explain an exciting framework used to analyze and generate sequences of chords in musical pieces. Before diving into the main part, I provide a brief introduction of the necessary concepts in music and harmony theory.

Music Theory - Chords and Scale Degrees

Playing the piano has always been one of my greatest passions. After playing classical music for several years, I fell in love with improvisation as well as playing songs in different arrangements and styles. However, compared to playing songs from scores, these skills require some knowledge about know music actually works. At its core, we can divide music into three fundamental concepts, namely melody, rhythm and harmony. While you surely have an intuitive understanding of what melody and rhythm are, you may not be quite familiar with the last one. We can basically put it like that: Melody questions which note is played after the other while harmony describes which notes can be played simultaneously. In western music, harmony is represented as a sequence of chords which in turn are notes that are picked from a certain scale.

The simplest form of a chord is the triad which consists of two stacked third intervals. For example, the C major chord contains the notes c, e and g which are derived by going a major third (four half steps) from c to e and a minor third (three half steps) from e to g. Similarily, we can define the three remaining triad types:

| type | first interval | second interval | example notation | example notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| major triad | major third | minor third | C | c, e, g |

| minor triad | minor third | major third | Cm | c, e♭, g |

| diminished triad | minor third | minor third | Cdim | c, e♭, g♭ |

| augmented triad | major third | major third | Caug | c, e, g♯ |

Have a listen to these chords to get a feeling of what they sound like. You might notice that the major triad sounds quite happy compared to the minor and the even darker diminished triad.

We can extend our chords by stacking another third on top of these triads. The resulting four-note chords are then called seventh chords. At this point, all thirds we stack on top of the seventh chords are called extensions or color tones. The resulting nineth, eleventh and thirteenth chords are especially used in jazz music and may sound very spicy.

The whole point of the theory of harmony is to put chords into a musical context. Most commonly in western music, this context is induced by the major or minor scale. A scale is just a set of notes that follow a specific interval pattern. For example, a major scale has seven notes which stack up in the following (repeating) interval sequence beginning from the root note:

whole step -> whole step -> half step -> whole step -> whole step -> whole step -> half step

In sheet music notation, the following represents the C major scale:

The minor scale follows a different pattern:

whole step -> half step -> whole step -> whole step -> half step -> whole step -> whole step

The C minor scale for example, looks like this:

Now, we can build so called diatonic chords from a scale. This means that we choose one of the notes in our scale as the root note and stack up thirds such that all resulting notes of our chord are also contained inside the scale. Let's say we're in the key of C major. A diatonic triad with the root e is a Em consisting of the notes e, g and h. Likewise, a diatonic triad with root b is a Bdim with notes b, d and f. The root note of a particular diatonic chord indicates its degree which we denote with roman numbers. For example, any chord that builds on F has degree IV because its the fourth chord in the C major scale. By convention, upper case roman numbers refer to major chords, while minor and diminished chords use lower case roman numbers. All diatonic triads over a C major scale with their respective degree are shown below:

Finally, you can go ahead and start making some music by playing any diatonic chords over a fixed major or minor scale. In fact, if you want to start a career as a pop musician, diatonic harmonies are sufficient to produce basic four-chord-songs played by famous interpreters such as Ed Sheeran. However, chord progressions in jazz and classical music are more complex and require a more thorough understanding of how that music was composed.

Functional Harmony

In the theory of Functional Harmony, each chord has a certain purpose or function in relation to a tonal center. In the context of a major or minor scale, the tonal center (also called the tonic) is the first degree of our scale. This starts to make sense when we introduce the dominant function, defined as the fifth scale degree. When played in a chord progression, the dominant wants to resolve to the tonic. Let's take a look at a the following vi-ii-V-I progression in C major:

First of all, you may wonder that these chords doesn't look like those from above. That is because in this example we used inversions of the chords which means that we simply shifted some notes an octave up or down. As long as the note names remain the same, we still talk about the same chord.

When you heard the G chord, you probably already had some expectations of what comes next. Notice that the C chord at the end sounds very satisfying and stable, like coming home.

As we enter the field of jazz, it's common to use seventh chords all the time. Here's the same chord progression but with seventh chords instead of triads (notice that the functions remain the same):

In addition to that, the IV and the ii serve a predominant (also called subdominant) function which prepares the dominant (the Dm7 in this example). If you play jazz, you'll definitely stumble upon the omnipresent ii-V-I progression.

It turns out that we can actually approach any chord from a fifth above with a dominant seventh chord. A dominant seventh chord is stacked up of a major third, a minor third and another minor third. The G7 in the progression is a dominant seventh chord for example. Using this principle, we can approach the Dm with an A7 dominant seventh chord instead of an Am7 as shown in the following example:

Note that the A7 is quite unusual because the c♯ does not belong to the key of C major. If a chord contains a note that isn't part of the current key, it is called a non-diatonic chord. As you can hear, the A7 leads more strongly to the Dm7 than the Am7 did. Therefore, the A7 is called a secondary dominant because it has a dominant function that leads to a chord which is not the tonic.

Functional harmony can explain progressions quite well which stay in the same tonal center and exhibit only limited non-diatonic occurrences. However, in classical music and jazz, we often observe chord sequences that are very difficult to come up with by using this theory (local key changes for example).

The Framework

Now, you're ready to learn about a very young theory invented by Martin Rohrmeier. Fortunately, I had the pleasure to meet him at a summer academy and I am excited to share what he taught at his lectures. In his theory, he generalizes the concepts of functional harmony to two core relations between chords, namely preparation and prolongation.

Preparations

In functional harmony, we said that a dominant chord resolves to the chord a fifth below. This is clearly one but not the only relation between two chords where a chord prepares another one. Other prepartory dependencies are for example:

- V-I

- ii-V

- iii-VI

- vii-I

- IV-V

The reason why we put them into a single category is because they share a common interpretation which is a goal-directed motion and the build-up and release of musical tension.

Prolongations

The second core relation between chords extends or prolongs the span of a given chord. The simplest form of prolonging a chord is by repeating itself but it could also be prolonged by its relative. For any major chord, its relative is the minor chord three half steps below its root. Likewise, for any minor chord, its relative is the major chord three half steps above its root. Here are some example prolongation rules:

- I-I

- V-V

- vi-vi

- I-vi (major chord prolonged by its relative)

- vi-I (minor chord prolonged by its relative)

Just like preparation relations, all prolongation rules have a common interpretation which is the temporal extension of a chord.

Recursive Derivation of Harmonic Sequences

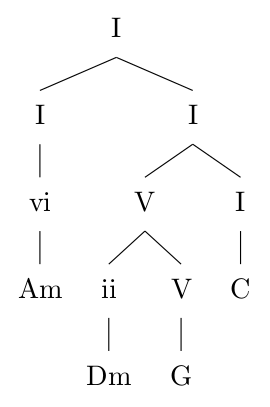

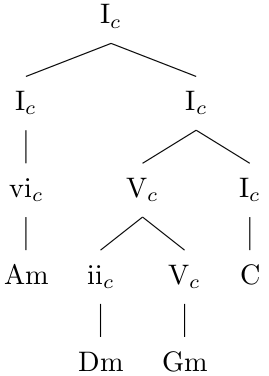

The core idea of Rohrmeier's framework is to use the rules of preparation and prolongation to create recursive derivations of harmonic sequences. In the following, we will learn how to derive the previous Am-Dm-G-C progression by recursively applying preparation and prolongation rules. An neat way to illustrate recursive derivations is to use trees. By doing so, a possible way to come up with the progression in question using Rohrmeier's Framework would look like this:

Recursive derivation of the Am-Dm-G-C progression.

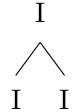

When reading the leaves from left to right, we get Am-Dm-G-C. So how does this work? Every derivation starts by branching out of the tonic. An interesting observation by Rohrmeier is that staying in the same key is basically a prolongation of the I. Put differently, a progression that remains in a certain key is a temporal expansion of the tonic. By doing so, we can depict a prolongation of the I as follows:

The I-I prolongation rule applied on the root node of the tree.

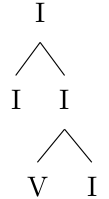

You might already see that the G looks like a preparation of the C. Given that C is our I, we can apply the V-I preparation rule on the right branch:

The V-I preparation rule applied on the right branch.

Next, we can recursively apply the ii-V preparation rule on the V:

Applying the ii-V preparation rule.

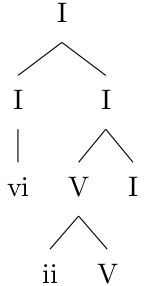

Then, according to the principle of prolongation as discussed before, we can substitute the left I by the vi:

Substitution of the I by the vi.

Finally, if we can derive the individual chords by passing the key as additional information to the nodes:

Passing key information.

Passing key information can be useful if a progression modulates (moves to another key). We may also leave out the key information if there doesn't occur any modulation as shown in the first tree.

Let's sum up what we just did: We introduced a method of expressing harmonic relations in a hierarchical manner by recursively applying only two core operations (preparation and prolongation). Then we derived the diatonic chord sequence Am-Dm-G-C using these rules in a tree-style fashion.

Expressing Harmonic Relations as Context-Free Grammar Rules

Our goal now is to create those derivations computationally by an algorithm. Therefore, we first have to formalize the preparation and prolongation rules. If you have any background in linguistic or theoretical computer science, you surely learned about context-free grammar. A context-free grammar contains a set of rules to generate the strings of a formal language. In our case, strings are chord progressions. A rule will have one of the following forms:

\[A \rightarrow B\]

\[A \rightarrow B\ C\]

\[A \rightarrow a\]

These rules mean that the symbol on the left is replaced by what's on the right hand side. There are two kinds of symbols: terminal and non-terminals. Only non-terminals can appear on the left side, meaning that a terminal cannot be further replaced anymore. In this example, a represents a terminal while A, B and C represent non-terminals.

Ok, enough theory - let's see how we can come up with context-free grammar rules which resemble preparation and prolongation rules. We will now define enough rules to derive the Am-Dm-G-C again. Let's start with the prolongation rule:

\[ I \rightarrow I\ I \]

When viewed in comparison to the trees, we can interpret the left hand side of a rule as a parent node whose child nodes are defined by the right hand side of the rule. Therefore, the preparation rule where the V prepares the I looks like this:

\[ I \rightarrow V\ I \]

Next, the I-vi substitution is defined as:

\[ I \rightarrow vi \]

Finally, we map the scale degrees to chord symbols which are our terminal symbols:

\[ I \rightarrow C \]

\[ ii \rightarrow Dm \]

\[ V \rightarrow G \]

\[ vi \rightarrow Am \]

That's it! Now, we can write a sequence of derivations using these rules to generate the Am-Dm-G-C progression:

\[ I \rightarrow I\ I \]

\[ I\ \color{red}{I} \rightarrow I\ \color{red}{V\ I} \]

\[ I\ \color{red}{V}\ I \rightarrow I\ \color{red}{ii\ V}\ I \]

\[ \color{red}{I}\ ii\ V\ I \rightarrow \color{red}{vi}\ ii\ V\ I \]

\[ \color{red}{vi}\ ii\ V\ I \rightarrow \color{red}{Am}\ ii\ V\ I \]

\[ Am\ \color{red}{ii}\ V\ I \rightarrow Am\ \color{red}{Dm}\ V\ I \]

\[ Am\ Dm\ \color{red}{V}\ I \rightarrow Am\ Dm\ \color{red}{G}\ I \]

\[ Am\ Dm\ G\ \color{red}{I} \rightarrow Am\ Dm\ G\ \color{red}{C} \]

Of course, we need a couple more rules to express every preparation and prolongation rule in all keys. So now we got a formal framework to generate musically coherent harmonic sequences. Even more interesting, we can take existing progressions and come up with derivations automatically using a parser. A parser is an algorithm, that takes grammar rules and a string (our progression) as input and outputs all possible derivation sequences of that string using the supplied grammar. This means, we can automatically generate trees to analyse any given chord progression! In fact, such a parser is fairly easy to implement but we won't go into that for now.

Conclusion

We only scratched the surface of it but I hope I could gave you a comprehensible introduction into Martin Rohrmeier's framework to generate and analyse harmonic sequences. For more advanced pieces, additional rules will be required which we haven't covered yet (for example substitution and modulation rules). In addition, one thing to keep in mind is that the presented method only produces coherent chord progressions. Generating entire pieces also involves incorporating melody and rhythm into the harmonic structure. We should also note that in music, played chords may not and don't have to be related to each other which Rohrmeier refers to as improper harmony! To conclude, I think the presented concepts are still quite impressive especially from a computer science perspective.